It’s a challenge for any company to efficiently invest in research and development (R&D) for advanced manufacturing applications. Costs are high and success is not a given. Joining industry peers in R&D to reduce risk also presents a dilemma: How do you help drive your company and the industry forward with technological innovation without sacrificing your proprietary information and differentiating applications? This dilemma applies across the spectrum of manufacturing, from global giants to tiny startups.

Companies are willing to share in the pain of addressing industry challenges that are bigger than any one entity. They are looking to collaborate with experts – whether they are from industry, academia or government – provided it is in a neutral, pre-competitive environment.

Private sector companies join institutes in the Manufacturing USA network to help de-risk and accelerate technology development. Institute members benefit from pooled R&D (sometimes with federal cost-sharing), access to expertise and state-of-the-art facilities with testing and prototyping equipment, and exposure to potential new partners. These Manufacturing USA institutes cover a wide range of technical domains, from biopharmaceutical production to composites, from robotics to cybersecurity.

“There is a high cost to build a proof of concept for new technology, and that cost is reduced in these facilities,” said Mike Shimauz, Smart Factory Technical Director at RTX Corporation, previously known as Raytheon Technologies, which is a member of six Manufacturing USA institutes. “We trust the process of protecting intellectual property (at the institutes), but there definitely are innovations that can be shared to help all of industry.”

Providing a Neutral Setting for Innovation

The institutes serve as a trusted third party for coming together to solve industry challenges. Many institute members are looking for a neutral setting for this pre-competitive collaboration, where joint R&D is conducted with the understanding that private sector company commercialization efforts will have to be conducted elsewhere.

“We are bringing government, industry, and academia together," says John Dyck, CEO of CESMII, the Smart Manufacturing Institute. “It’s a convening of the best thinkers – manufacturers, designers, machine builders, and integrators. We are working together to accelerate the democratization of smart manufacturing.”

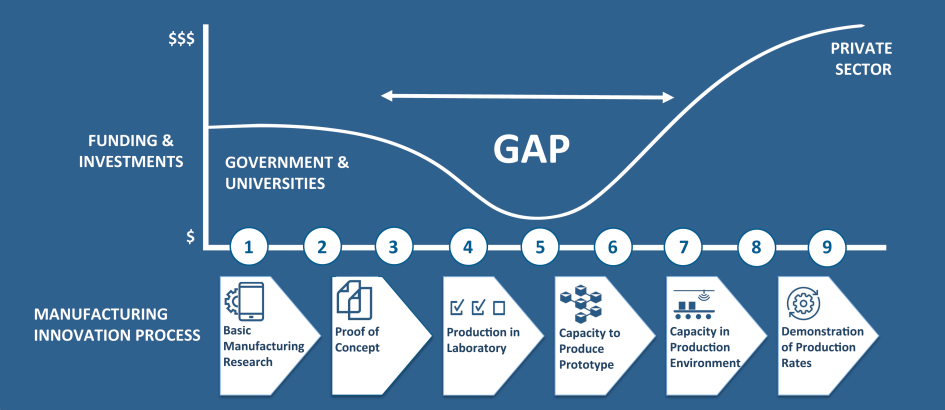

The institutes share the common purpose of solving proof-of-concept problems in order to scale manufacturing. But their projects vary greatly in their Manufacturing Readiness Level (MRL), which many companies refer to as Technology Readiness Level (TRL). For example, some projects are closer to the idea stage, such as dealing with a laboratory demonstration of a new application (MRL 4). Other projects are much closer to commercialization, such as implementing innovation in a production environment (MRL 7).

There are other factors driving collaboration as well, such as:

- While big competitors compete on some fronts, they are also dependent on a shared supply chain. To some extent, they must cooperate to nurture technological advancement in the supply chain in order to effectively compete.

- Forging agreements on standards for new technology will benefit the marketplace, such as with charging stations that accommodate different brands of electric vehicles.

- Not everything worth sharing is patentable or considered proprietary. There is a lot of value in information learned from early adoption and experimentation, such as best practices or even what settings to use on a machine under various conditions.

Additionally, a one-size-fits-all approach is not sufficient for protecting intellectual property (IP) during collaboration. This is why the institutes have customized their IP guidelines. For example, an institute might own the IP developed in one of its projects and license it to companies. Or the companies participating in a project get access to IP for free or at a special partnership rate. Some institutes share IP among project participants or with all of their members. Some institutes allow the companies working on a project to own the IP.

Creating a Level of Comfort for Competing Members to Collaborate

The RAPID Institute, which works with large-scale, emissions-intensive chemical processes, recently launched a product that includes industrial giants Dow, Shell USA, and Siemens USA, among the 12 participating companies. “Dow and Shell have worked together in Europe,” says Ignasi Palou-Rivera, RAPID’s Chief Technology Officer. “Big companies are becoming more comfortable working with each other under the right conditions.”

The project also includes three universities, one national lab, several non-profits, and a couple of start-up companies. The project focuses on scaling up electromagnetic reactors to use microwave (MW) and radio frequency (RF) energy instead of conventional thermal energy to decarbonize commodity chemical production.

Using MW and RF energy has many potential benefits, including higher energy transfer efficiency, uniform heating, and reduced need for equipment. The vision is to enable more distributed manufacturing – the ability to process chemicals more efficiently at more and smaller locations. It’s similar in nature to using many micro-grids to generate electricity as opposed to giant power plants. It’s a big shift in how the industry operates.

“We are IP neutral; we are all about creating a level of comfort for our members. We make sure IP belongs to whoever creates it. We give companies participating in the project opportunities to license IP if it is created in the project.” - Ignasi Palou-Rivera

Palou-Rivera emphasizes that they have research partners and members for whom IP is critical. In some cases, proprietary applications are used for R&D within a project but must be licensed for commercial use. RAPID strives to provide project participants with equal status in a project. For example, some members want physical development conducted at a neutral site, not at another company’s facility.

Enabling Possibilities, Not Product Development

NextFlex and the other institutes must be driven by longer-term objectives and where the industry is headed in terms of manufacturing capabilities, says Dr. Scott Miller, the Director of Technology at the institute dedicated to Flexible Hybrid Electronics.

“We exist with the intention of living in a pre-competitive space,” Miller says. “It’s not product development. We are about developing the enablement and possibilities for products.”

NextFlex’s IP policy, which every member agrees to, creates a collaborative zone where members are comfortable sharing pre-competitive work and ideas for the benefit of the member community. Miller summarizes the principles of the IP policy as:

- Information about work and outcomes is shared with all members via regular reports and webinars. There is a lot of valuable information learned in each project, which members can often put to use at their organization.

- Developers own the IP. If you invent it, you own it. However, you still have to tell the members about what you have developed and the outcomes of the project.

- Every NextFlex member gets an “internal evaluation license.” They cannot do anything commercial with the license, but they can go back to the developers and negotiate a licensing agreement. (There are general licensing terms in contracts that obligate reasonable and non-discriminating terms.)

“If we were to require open use, people wouldn’t work on things that are really valuable,” Miller says. “However, if you have a secret sauce, don’t involve it in the project. There are other avenues for that kind of R&D.”

A NextFlex project call typically identifies a gap or a need, perhaps seeking a material with a certain property or trying to find a way to attach components in a specific environment. Solutions need to apply broadly in order to benefit the industry. Members can contribute as many subject matter experts to a project as they want. NextFlex encourages collaboration to generate better ideas. Companies may not agree on every aspect of the project, but they can benefit from some portion of it.

Entire Pharma Industry Benefits from NIIMBL-led Project on Buffer Stock

An example of successful pre-competitive collaboration comes from the pharmaceutical industry and its reliance on buffer stock for testing. Producing buffer stock traditionally has taken considerable time and facility space, so everyone in the industry would benefit from a more efficient process as it would allow companies to devote more resources to developing new products and proprietary research.

The NIIMBL institute led a project in collaboration with BioPhorum and industry giants Merck & Co., MilliporeSigma, Janssen Research & Development, Sanofi, and GlaxoSmithKline to develop a new buffer blending stock system. The technology reduces the time it takes to manufacture 2,000 liters of buffer solution from eight hours to less than an hour, which leads to a huge increase in testing capacity and a significant reduction in the cost of a sample.

By working together through NIIMBL to share feedback and costs, the competitors were able to achieve success faster and more efficiently than if any of them had done the work alone.

Automakers Turn to CESMII for Smart Manufacturing Roadmap

The automotive industry also benefits from pre-competitive collaboration enabled by institutes. While automakers compete for customers they all share a domestic supply chain that must increase its resilience and productivity. Automakers are looking for a more collaborative approach to address these challenges.

This is where CESMII, the Smart Manufacturing Institute, comes in. CESMII is working with USCAR (United States Council for Automotive Research) to help automakers rethink the way they use data to empower people and inform strategies, for operations and for resource planning and predictions.

USCAR hosted the Automotive Smart Manufacturing Summit in August 2023 with about 100 manufacturing stakeholders, including representatives from Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis. They worked together to develop the Smart Manufacturing Roadmap for Automotive, which is being introduced to the industry in April. The roadmap focuses on three vital strategies:

- Collaborate via real-time, data-driven digital processes that are connected within plants and across the value chain.

- Enable data interoperability based on standardized, open interfaces that eliminate silos and restricted architectures.

- Develop a Smart Manufacturing Mindset™, aligning education, workforce development, and continuous improvement strategies to create data-driven cultures.

“Smart manufacturing is a critical enabler for advancing and improving U.S. automotive manufacturing processes,” says Dr. Steven Przesmitzki, Executive Director of USCAR.

Helping Accelerate the Democratization of Advanced Manufacturing

The pre-competitive collaboration efforts across the Manufacturing USA network are essential to strengthening the competitive position and technical leadership of U.S. manufacturing companies. These collaborations are also providing pathways to Americans seeking rewarding, living-wage jobs and are contributing to stronger local, regional, and national communities.

In 2022, the institutes collectively worked with over 2,500 member organizations to collaborate on more than 670 major technology and workforce research and development projects, and engaged over 106,000 people in advanced manufacturing training. State, industry, and federal funds contributed $416 million to these activities.

To learn about the many ways institutes are helping de-risk investments in advanced manufacturing applications, visit our institutes page.